Financing Campaigns

by Marc Schulman

The cost of financing campaigns has steadily risen over the last few decades. In 1975-76, $100 million dollars was spent on congressional election campaigns. By 1995-96, that number had grown to $766.4 million. Direct spending in presidential campaigns has risen in the same period from a little over $100 million to $400 million, and this does not even include the amount spent by independent groups and state and national campaigns. Since it has not been affected by prior attempts at campaign finance reform, spending in state and national campaigns has grown even more significant.

Under terms of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, individuals are limited to making contributions of $1,000 per candidate per election, $5,000 a year to a political action committee (PAC) and $20,000 a year to a political party. In total, an individual cannot donate more than $25,000 to an election campaign. In addition, the act provides for public funding of the presidential campaigns of the major parties.

The effectiveness of the Campaign Act has been greatly reduced by two Supreme Court decisions. The first is Buckley v. Valeo (1976), in which the Court held that individuals could not be made to accept campaign limits. Spending money on a campaign was the equivalent to free speech. Candidates can only have their spending limited if they enter into agreements to limit spending by taking federal campaign funds. In 1996, in the case of Colorado Republican Federal Campaigning Committee v. Federal Election Commission, the Court held that state and local parties cannot be limited in the amount of money spent on behalf of candidate, as long as that spending is not coordinated with the candidate. This extends to PACs and other equivalent groups.

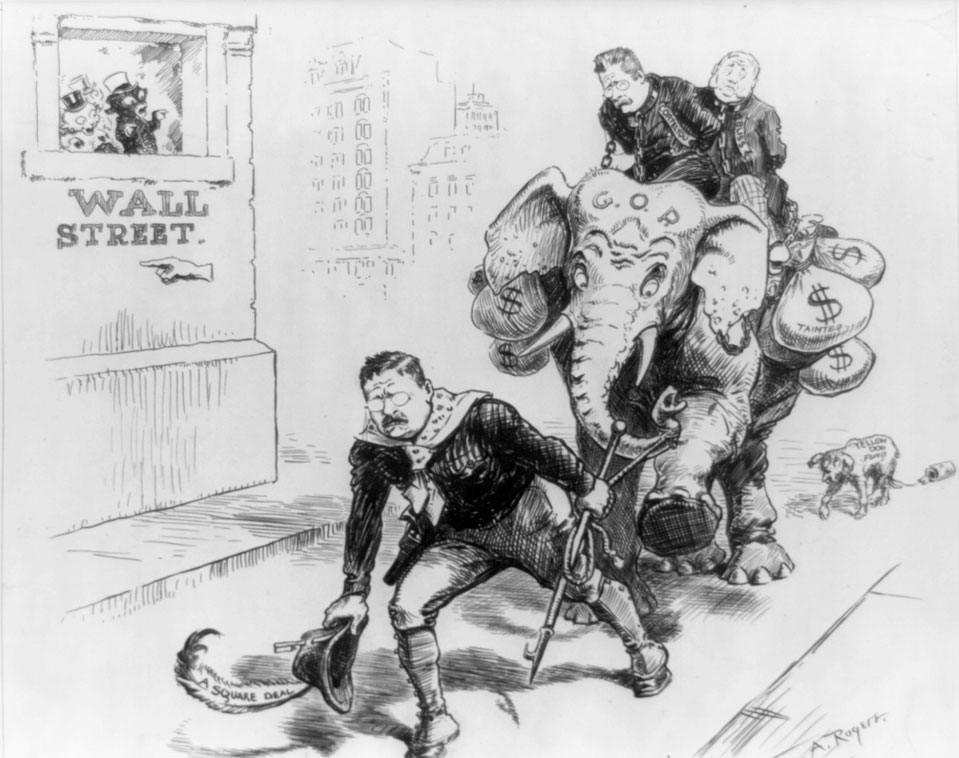

The need for so much money in political campaigns has resulted in an unseemly pursuit of money. A candidate for the House of Representatives needs to raise nearly $2,000 every day. A Senator needs more than three times that amount. Thus, Congresspeople feel that they must offer access to their offices in return for donations. The practice was taken to its logical extreme in the 1996 presidential campaign, during which donors to the Democratic Committee were promised tea with the Clintons or, in some cases, an opportunity to sleep in the Lincoln bedroom in the White House.

The cost of camaigna has continued to skyrocket with the $4.2 billion spent in the 2004 campaign and $5.3 spent in 2008

To most observers of the system, the need for significant campaing reform is clear. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to bring about significant campaign reform, because of the position of the Supreme Court, which has equated spending money with free speech; and the opposition of people who benefit from the current system.

>

>