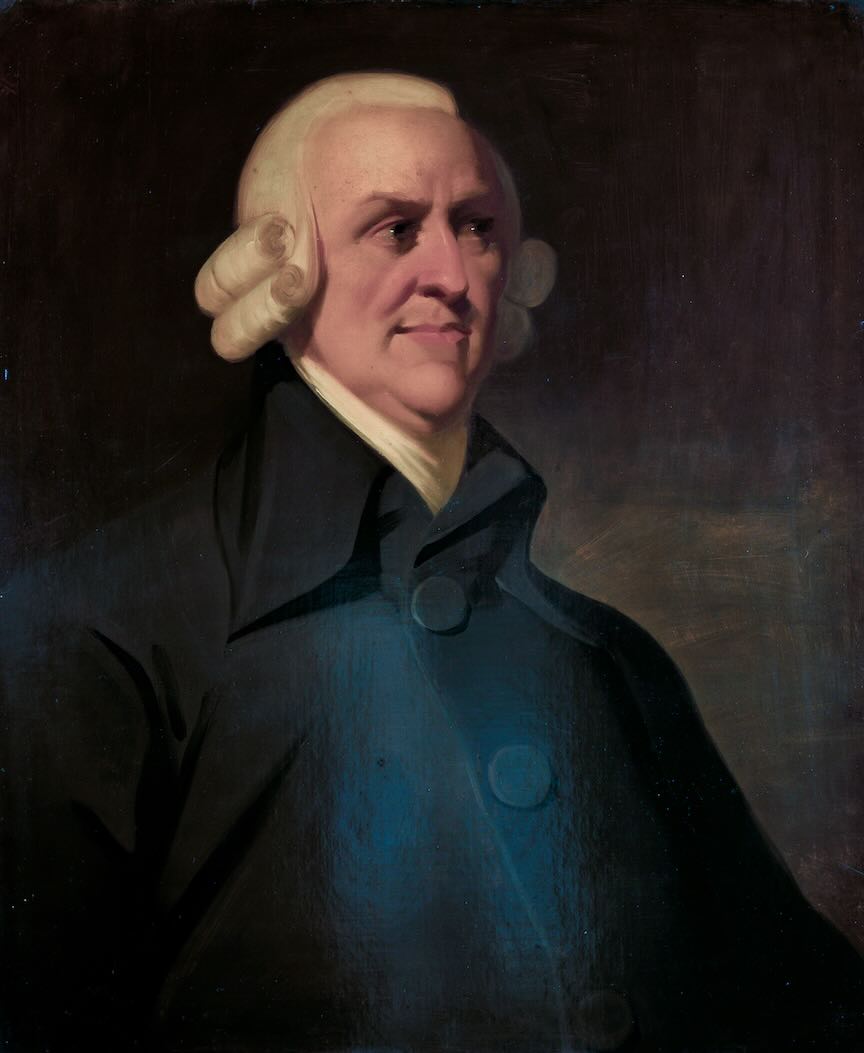

Adam Smith, renowned for The Wealth of Nations (1776), is considered the father of modern economics. As a professor of moral philosophy, Smith developed the idea that individuals pursuing their own economic self-interests, without government intervention, would benefit society as a whole through the “invisible hand.” His work laid the foundation for laissez-faire economics, influencing future economic thought and policy..

Adam Smith, born in 1723 in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of economic thought. He is often referred to as the “father of modern economics” for his groundbreaking work in political economics, particularly his seminal book, The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. Smith’s ideas would go on to form the foundation of classical economics and continue to influence economic policy today.

Smith’s education began at a young age. After attending the Burgh School of Kirkcaldy, known for its excellent curriculum in Latin, mathematics, and writing, he entered the University of Glasgow at age 14. It was there that he studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson, an influence that helped shape Smith’s future ideas about human nature, ethics, and economics. Smith later attended Balliol College, Oxford, where he furthered his studies in philosophy and the humanities.

In 1751, Smith returned to the University of Glasgow as a professor of logic. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed to the prestigious chair of moral philosophy. His lectures covered a wide range of subjects, including ethics, rhetoric, jurisprudence, and political economy. It was during his tenure as a professor that Smith wrote his first major work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). In this book, Smith explored the nature of human morality and introduced the concept of sympathy as a central component of ethical behavior. He argued that individuals are naturally inclined to act in ways that promote social harmony, a theme that would later be expanded in his economic theories.

Smith’s most famous work, The Wealth of Nations, revolutionized the field of economics by presenting a comprehensive theory of free markets and laissez-faire policies. In it, Smith contended that individuals, when left to pursue their own economic self-interests without government interference, would unintentionally promote the good of society. He coined the metaphor of the “invisible hand” to describe this phenomenon, asserting that the pursuit of personal gain would lead to efficient resource allocation and overall societal benefit. This concept became the foundation for the laissez-faire economic philosophy, advocating minimal government intervention in markets.

Smith’s influence extended beyond economics. In addition to The Wealth of Nations, he wrote essays on subjects such as the arts, linguistics, logic, classical physics, and astronomy, showcasing his wide-ranging intellectual curiosity. Throughout his life, Smith remained dedicated to public service. In 1778, he was appointed commissioner of customs for Scotland, a position that allowed him to apply his economic principles to practical governance. He also served as lord rector of the University of Glasgow, demonstrating his continued commitment to education and scholarship.

Smith was highly regarded by his contemporaries, admired for his intellect and moral character. One famous anecdote highlights this admiration: during a dinner, the British Prime Minister requested that Smith be seated first, remarking, “We are all your scholars.” This acknowledgment reflected the profound impact Smith’s ideas had on both intellectual circles and policy-makers of his time.

Adam Smith passed away in 1790, but his work endures.

>

>