Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of France’s most renowned authors and philosophers, argued that civilization corrupted humanity’s natural goodness and restricted freedom. His 1762 work The Social Contract introduced the famous phrase “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains,” inspiring the French Revolution. Despite his literary success, Rousseau struggled with mental health and spent his final years in turmoil before his death in 1778.

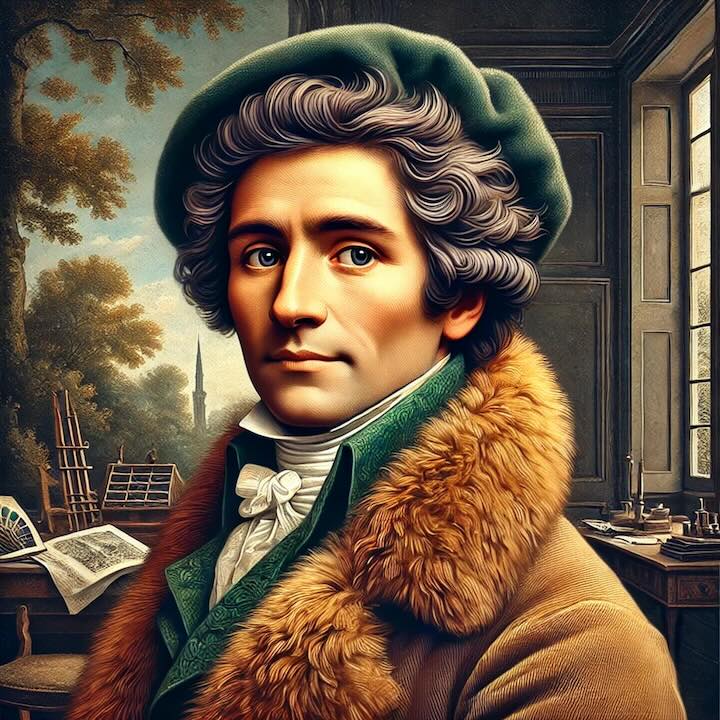

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, born on June 28, 1712, in Geneva, Switzerland, is remembered as one of the most influential philosophers of the Enlightenment and a key figure in shaping modern political thought. Though born into a modest family, Rousseau’s early life was marred by instability. His mother died shortly after his birth, and his father, a watchmaker, abandoned him at a young age. As a result, Rousseau received little formal education and led a somewhat rootless existence in his youth. Despite these hardships, he had an insatiable desire for knowledge and educated himself through voracious reading and self-study.

Rousseau’s philosophical and literary career began in the 1740s when he moved to Paris and mingled with intellectuals like Denis Diderot. He gained recognition with his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750), in which he argued that the progress of civilization had led to the moral degradation of humanity, a bold rejection of the prevailing Enlightenment belief in the virtues of progress. His central thesis was that humans were naturally good, but society’s constraints led to corruption and inequality. This idea would come to define much of Rousseau’s work.

In 1762, Rousseau published The Social Contract, one of his most important and influential works. Its opening line, “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains,” is among the most famous in political philosophy. In the book, Rousseau argued that legitimate political authority derives from the consent of the governed and that a society’s laws must reflect the general will of its citizens. His ideas about liberty, equality, and fraternity—concepts that would later become the rallying cry of the French Revolution—emphasized a deep commitment to social justice and the collective good. Though radical at the time, Rousseau’s work laid the groundwork for much of modern democratic thought.

Despite his philosophical brilliance, Rousseau’s personal life was turbulent. After The Social Contract was condemned by the authorities, he fled France, seeking refuge in England under the sponsorship of Scottish philosopher David Hume. However, his stay in England was short-lived. Rousseau quarreled with Hume and became increasingly paranoid, believing that Hume and others were conspiring against him. His mental health began to deteriorate during this period, a decline that worsened after his return to France in 1767.

In the years following, Rousseau continued to write, producing works such as Confessions (published between 1782 and 1789), an introspective autobiography that offered candid reflections on his life. Yet, as his mental state became increasingly unstable, Rousseau withdrew from public life, spending his final years in relative seclusion.

Rousseau died on July 2, 1778, in Ermenonville, France. Sixteen years after his death, amid the French Revolution that his ideas had helped inspire, Rousseau’s remains were moved to the Pantheon in Paris, where he was interred beside Voltaire, another towering figure of the Enlightenment. Today, Rousseau is celebrated for his profound influence on political philosophy, literature, and education, particularly his vision of human freedom and equality.

>

>