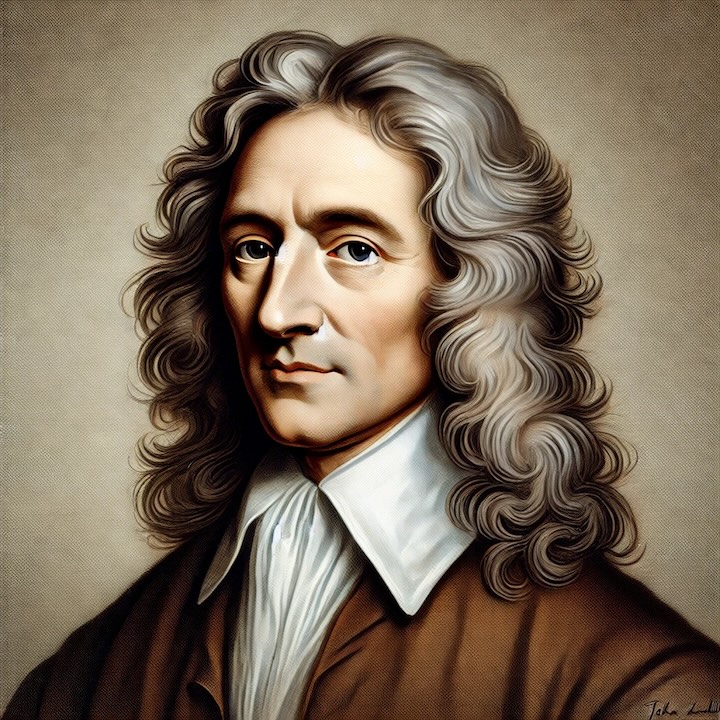

John Locke, an English philosopher and empiricist, is best known for his “Two Treatises of Government” (1690), where he argued for the social contract, natural rights, and constitutional law over absolutism. Locke’s ideas influenced the American and French revolutions, advocating rebellion against unjust rulers. His philosophy also posited that all knowledge derives from sensory experience, promoting tolerance and moderation..

John Locke was born on August 29, 1632, in Wrington, Somerset, England, into a Puritan family. His father was a lawyer and a captain in the English Civil War, which deeply influenced Locke’s views on authority and governance. Locke was educated at Westminster School and later attended Christ Church, Oxford, where he studied classical languages and philosophy. However, Locke found the curriculum unsatisfying and was particularly critical of the scholastic emphasis on classical texts rather than empirical observation.

During his time at Oxford, Locke became increasingly interested in medicine and natural sciences, and he later studied under the prominent physician Thomas Sydenham. This medical background not only shaped Locke’s scientific approach to philosophy but also connected him with key figures in England’s intellectual circles. Locke became involved with the Earl of Shaftesbury, a prominent political figure, and served as his personal physician and advisor. This association led Locke to develop his ideas on government, liberty, and natural rights, particularly in response to the political upheavals of the time, including the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Locke spent several years in exile in the Netherlands during the reign of King James II, who pursued policies that threatened the constitutional order of England. During his exile, Locke wrote many of his most important works, including Two Treatises of Government and An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. After the Glorious Revolution, when William of Orange ascended to the English throne, Locke returned to England, where he published his works and became more involved in intellectual life.

Locke never married and lived a relatively private life, though he was highly influential through his writings and correspondence.

His work laid the intellectual foundation for many modern democratic governments, especially through his ideas on natural rights, government by consent, and empiricism. Locke’s contributions significantly shaped Western political thought, particularly through his most famous political work, Two Treatises of Government (1690).

In Two Treatises of Government, Locke rejected the notion of absolute monarchy and the Divine Right of Kings, both of which were widely accepted in his time. He argued instead for a social contract—a voluntary agreement between the people and their government. According to Locke, the primary purpose of government is to protect the natural rights of individuals, specifically life, liberty, and property. He believed that these rights were inherent and not granted by any monarch or authority. Locke’s vision of government was rooted in the idea that it should function as an instrument of natural law, and if a government failed to uphold this duty, it was the right—and even the obligation—of the people to replace it. This stance provided a philosophical basis for resistance to tyranny and justified rebellion when rulers acted unjustly.

Locke’s ideas had a profound influence on the political movements of the 18th century, particularly the American and French revolutions. His notion of natural rights and the right to revolt against unjust governments resonated with those seeking independence and liberty. In the American Revolution, leaders like Thomas Jefferson drew directly from Locke’s work when drafting the Declaration of Independence, which explicitly asserts the right of the people to overthrow a government that fails to secure their rights. Similarly, Locke’s work influenced the French Revolution, where his ideas on equality and resistance to oppression helped inspire calls for political change.

Beyond politics, Locke made significant contributions to epistemology, the study of knowledge. His major work on this subject, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), posited that all knowledge comes from sensory experience. He famously stated that the mind is a “tabula rasa” or blank slate at birth, and that knowledge is acquired through experience and reflection. This empiricist approach marked a departure from the rationalist philosophy dominant at the time, which held that some knowledge was innate or independent of experience. Locke’s ideas on human understanding influenced later philosophers such as David Hume and Immanuel Kant, as well as the development of modern psychology.

Locke was also known for his moderate and tolerant views, particularly in matters of religion. In A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), Locke argued for religious tolerance and the separation of church and state. He maintained that the state should not have the authority to impose religious beliefs on individuals and that religious diversity should be accepted, as long as it did not threaten public order. His views on tolerance, though progressive for the time, had limitations; for example, Locke did not extend this tolerance to atheists or Catholics, whom he viewed as potentially subversive to the social order.

In sum, John Locke’s legacy as a philosopher is immense, with his ideas on government, human rights, knowledge, and tolerance deeply influencing both the Enlightenment and the shaping of modern democratic societies. His work remains foundational in understanding the principles of liberal democracy, individual rights, and the rule of law. Through his advocacy of empiricism, Locke also contributed significantly to the development of modern scientific and philosophical inquiry, placing experience and observation at the center of knowledge.

He spent his later years at the home of Sir Francis Masham, a friend, and philosopher, where he continued to write until his death on October 28, 1704.

>

>