Roosevelt and the Winds of War

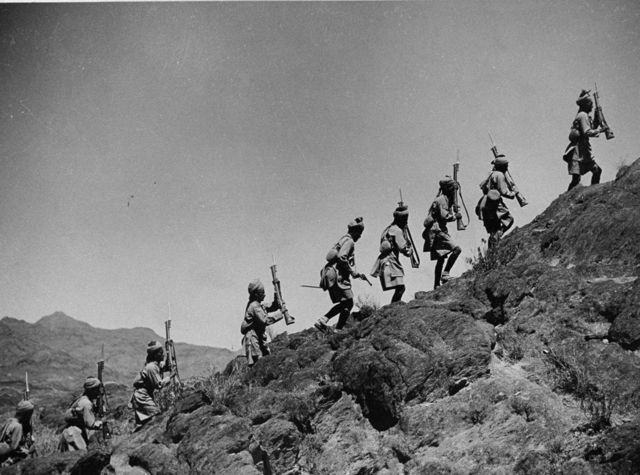

Ethiopia

While Roosevelt tried to concentrate on domestic events, affairs of the world intervened. Nazi Germany announced in March 1935 that it was renouncing the disarmament clauses of the Versailles agreement. In October, the Italians attacked defenseless Ethiopia. Meanwhile, Roosevelt had to contend with increased isolationism, which forced him to support the Neutrality legislation. In July of 1936, a rightist revolt in Spain heralded the start of the Spanish Civil War. By 1937, the Japanese renewed their attacks

.

By renouncing the disarmament provisions of the Versailles treaty in 1935, Hitler took the first step to war. Nazi Germany began openly rebuilding its armed forces. The Italian onslaught and capture of Ethiopia by Mussolini in October, was strongly condemned by the League of Nations. At the same time, Congress, under strong pressure from the isolationists, passed the Neutrality Act, which forced an arms embargo on belligerents in a war. Roosevelt attempted to convince the Congress to grant him discretionary powers. Unable to completely sway Congress towards his position, the President agreed to the complete embargo, especially in light of the fact that in the case of the Italian attack on Ethiopia, the embargo would hurt the aggressors more than the Ethiopians.

Roosevelt sought a way to intervene but knew his options were limited. He wrote to Colonel House (President Wilson's assistant) in April 1935: I am of course, greatly disturbed by events on the other side, perhaps more than I should be. I have thought over two or three different methods by which the weight of America could be thrown into the scale of peace and of stopping the armament race. I rejected each in turn for the principle reason, that I fear any suggestion on our part would meet with the same kind of chilly, half contemptuous reception on the other side as an appeal would have met in July or August, 1914

Right-wing Spanish officers led by Franco revolted against the legitimate government of Spain in July 1936. The Germans and the Italians aided the rebels, while the French and the British refused to help the loyalist government, fearing provocation of the Germans. Roosevelt announced a moral embargo on the belligerents, and then quietly supported an amendment to the Neutrality Act that extended it to civil wars. Thus Roosevelt could avoid taking sides - an action that would have negative political consequences. Later in the war, as his sympathies shifted more strongly to the loyalist government, he would regret this decision.

In July of 1937, the Japanese used the pretext of a created incident at the Marco Polo Bridge to resume their attacks in China. Roosevelt was incensed and looked for a way to respond. In Chicago he gave a speech asking to quarantine the aggressors. He was vague and did not give details as to what quarantine was. It was, however, Roosevelt's strongest foreign policy speech. It resulted in a hail of criticism by the isolationists and therefore Roosevelt went no further.

>

>