Battle of Shiloh

More soldiers died in the Battle of Shiloh than had died in all of America's Wars up until that moment. The Union General - Grant prevailed in what was but a preview of the bloody days ahead.

.

General Albert Johnson, Commander of Confederate troops in the West, resolved to attack Union troops led by General Grant– before his forces could be combined with those commanded by General Buell. General Johnson led his troops from Corinth towards Pittsburg Landing. Johnson's troops were green. This march, which later in the war would have been accomplished in one day, took three days. By the time Confederate troops neared the Union lines, General Beauregard, second in command, was convinced the attack should be called off– since all chance of surprise had been lost, due to the length and noise of the advance.

Beauregard was wrong, however. Despite evidence of a Confederate advance, Union generals (especially Grant and Sherman, who were in charge of the camp,) did not believe the Confederates were capable of mounting a successful attack. When one regiment commander sent repeated messages that the Rebels were massing for an attack, Sherman came out to see the regiment. He told the regiment commander: “Take your regiment back to Ohio, Beauregard is not such a fool as to leave his base of operations and attack us in ours. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth.”

The next morning Sherman would discover how wrong he had been. The assault began early in the morning. It began almost by accident, when a Confederate reconnaissance party ran into Union pickets. The assault was soon joined. Both Union and Confederate soldiers fought hard. However, the Union line was slowly pushed back. Grant, who had been away from Pittsburg landing when the fight began, was soon back rallying his troops.

As General Prentice’s troops were forced back, they came across an abandoned wagon road. This became known as “the sunken road”, where they made a stand. General Grant came by and approved of the position, telling Prentice to hold it “at all cost”. Prentice's troops did indeed hold the position. This position, which also became known as “Hornet’s Nest”, was held throughout the day, suppressing the Confederate advance. Toward evening, the surrounded soldiers stationed in the Hornet’s Nest were forced to surrender, including their commander General Prentice.

By then, however, it was too late for the Confederates to win, for two things had happened. First, the Confederate commander, Albert Johnson, who had spent the day at the front exhorting his troops, was struck and killed by a Union bullet. Beauregard, who assumed command continued the attack. By then, day was turning into night, and many of the Confederate troops had stopped to loot the overrun Union camp. Second, and more importantly, was the arrival of Union reinforcements, and the fact that the Confederate advance brought them within range of Federal gunboats.

With the onset of darkness, Beauregard called off the attack for the night. The Confederates planned to resume the battle in the morning, with the expectation of a quick victory. Grant, despite the heavy losses, was equally as confident the Union would prevail– and with good reason. The army of General Buell had arrived with 20,000 fresh troops. In addition, the 6,000 soldiers in General Lew Wallace's division had not taken part in the first day’s battle. These additional Union troops were all alert and primed to fight.

The next morning Union forces counterattacked. They rapidly advanced against surprised Confederate troops. The Confederates recovered their composure, and put up a stiff defense. However, their troops were bone weary, and the Union troops were mostly fresh. Finally, Beauregard concluded that there was no choice but to withdraw. Soon the order was given and Confederates troops began to withdraw to Corinth.

This was the bloodiest day of the war to date. There were more casualties in one day of the battle at Shiloh (i.e. 23,741), than were suffered in all of America’s previous wars.

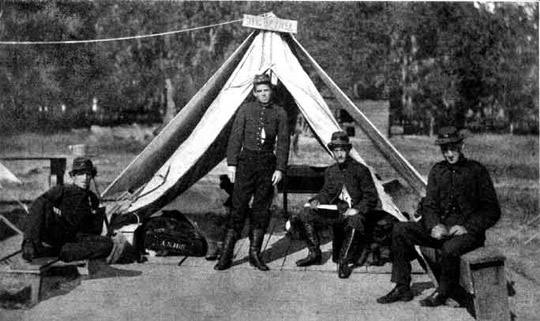

This is a photo of the 9th Indiana before the battle.

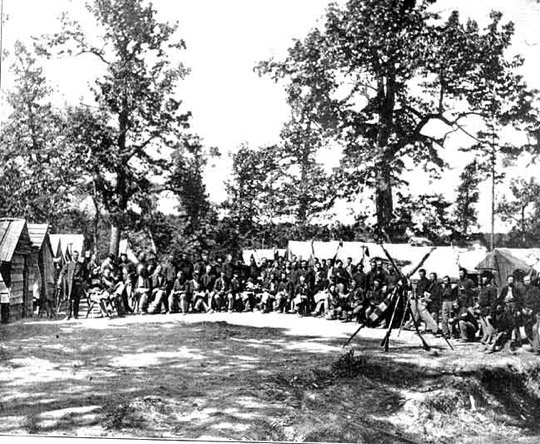

This is a photo of Confederate Soldiers before the battle.

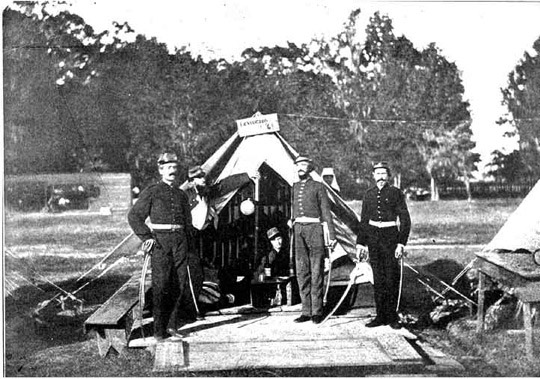

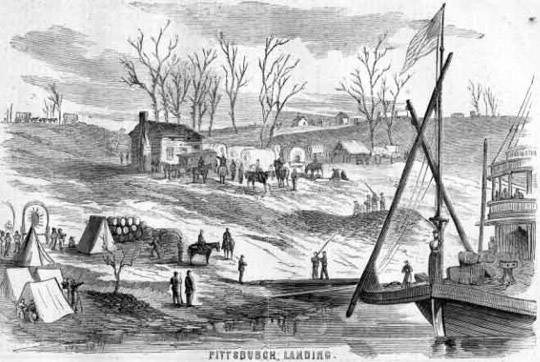

This is a drawing of Union troops coming ashore

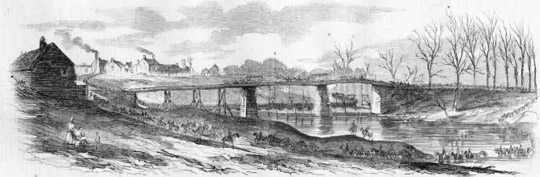

This illustration from Harpers Weekly from May 3, 1862 captioned:General Buell's Army Crossing Duck River, At Columbia, Tennessee, To Reinforce General Grant.—sketched By Mr. H. Mosler

>

>