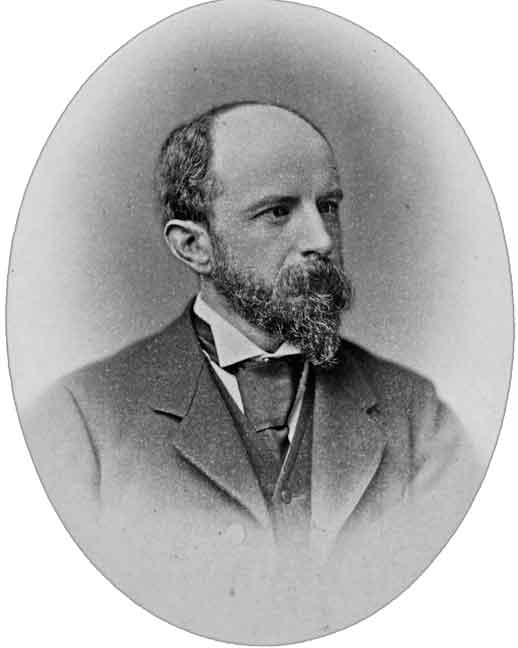

Henry Brooks Adams was born on February 16, 1838, in Boston, Massachusetts, the great-grandson of President John Adams, grandson of President John Quincy Adams and son of railroad executive and historian Charles Francis Adams. Young Adams graduated from Harvard College in 1858, then went on to study law briefly in Berlin and travel in Italy and France. Upon his return to the United States, he worked for his father, then became a member of the US House of Representatives. In 1861, when his father went to England as the new US minister to England, young Adams accompanied him, serving as his personal secretary.

In 1868, after returning to the United States, he worked as a journalist in Washington, D.C., then became an assistant professor of mediaeval history at Harvard in 1870. At Harvard, he introduced the seminar method of study, and attempted to use a "scientific" approach to teaching history. From 1870 to 1876, he edited the prestigious North American Review. He also he edited Essays in Anglo-Saxon Law (1876) and Documents Relating to New England Federalism, 1800-1815 (1877). In 1879, he published two works on former Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin: The Life of Gallatin and The Writings of Albert Gallatin. Other works include the anonymously published satirical novel, Democracy (1880), the critical biography John Randolph (1882), the pseudonymously published novel Esther (1884), the epic History of the United States During the Administrations of Jefferson and Madison (9 volumes, 1889-91) and the privately distributed A Letter to American Teachers of History (1910). Adams traveled abroad for many years after his wife’s suicide in 1885.

By the turn of the twentieth century, he was a leading figure in Washington society and a friend of politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt. In 1904, he published a study of the concept of unity in the Middle Ages, entitled Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres. His most widely known work, the autobiography The Education of Henry Adams, was privately printed in 1904, but was not publicly released until 1918. Adams saw his autobiography as a "study of twentieth-century multiplicity," a sort of sequel to Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres. He asserted that society had to train new leaders via scientific means in order to maintain control over technology, to prevent the expansion of technology from overcoming civilization. Although it was not a significant success to contemporary readers, the work later established him as one of the great American writers and historians. Adams died in Washington, D.C., on March 27, 1918.

>

>