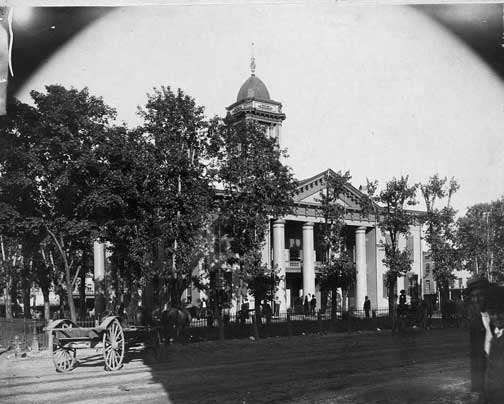

Charleston Court House

President Jackson signed into force a tariff that was more moderate then the previous Tariff of Abomination. The tariff was too high for South Carolinia, who declared the tariff null and void. Jackson warned that nullifcation was equivilant to treason and he received Congressional authorization to collect the tariff by force if neccessary.

The Crisis of Nullification began with the passage of the Tariff of Abominations in 1828. This tariff was designed to both protect the nascent American manufacturing industries in the North and to bring in additional income to the Federal government. The Tariff of Abominations was especially unpopular in the South, whose economy was primarily based on cotton exports and who imported much of their day-to-day goods. The Southern states felt the Tariff of Abominations unfairly penalized them and favored the North.

South Carolinians were struggling financially and felt particularly aggrieved by the tariff. Their leading advocate, Vice President Calhoun, was out of favor with Jackson and could do little to help directly. In the summer of 1828, Calhoun quietly wrote the “South Carolina Exposition,” a treatise attacking the tariffs as unconstitutional. Calhoun further claimed that states had the right to void unconstitutional acts, stating: “But the existence of the right of judging of their powers, so clearly established from the sovereignty of States, as clearly implies a veto or control, within its limits, on the action of the General Government, on contested points of authority; and this very control is the remedy which the Constitution has provided to prevent the encroachments of the General Government on the reserved rights of the States; and by which the distribution of power, between the General and State Governments, may be preserved forever inviolable, on the basis established by the Constitution. It is thus effectual protection is afforded to the minority, against the oppression of the majority...”

Calhoun contended that the tariffs were unconstitutional, as the right to impose tariffs granted by the Constitution was solely for the purpose of raising revenue—not protecting domestic industries. By 1831, Calhoun was sufficiently frustrated that he decided to go public with his views on the nullification of the tariffs. In his Fort Hill Address, he reiterated much of what he had written in the South Carolina Exposition, adding that he believed the Judiciary were not the arbiters of the Constitution.

The Jackson administration was worried about the direction Calhoun was pushing South Carolina. Jackson was ambivalent about tariffs himself and would not have minded seeing the Tariff of Abominations lowered. However, he certainly did not accept Calhoun’s view on state supremacy. The recently defeated president, John Quincy Adams, stepped in to save the day. Adams returned to Washington as a member of the House of Representatives and was made Chairman of the Committee on Manufactures due to his stature. Adams took his responsibility seriously and tried to work out a compromise that satisfied both the North and South. He put together a bill that moderately reduced tariffs on items not produced in the US and drastically lowered the tariffs on cheap woolen items (material from which slave clothing was made). The bill, known as the Tariff of 1832, was overwhelmingly approved with significant southern support. Adams seemed to have successfully put the issue of tariffs to rest.

The Tariff of 1832 settled the issue for the rest of the South, but it failed to do so in South Carolina. To South Carolinians, the largest slave-holding state, the issue of tariffs reflected larger issues of state rights and the fear that the federal government could take actions against slavery. On November 24, 1832, South Carolina held a Nullification Convention where it was declared that the tariffs of 1828 and 1831 were unconstitutional and would no longer be in effect in South Carolina starting in January 1833.

Jackson's response was swift. In a proclamation issued two weeks later, Jackson claimed that nullification was equivalent to secession, which could only be done by armed force. He stated, “Do not be deceived by names. Disunion by armed force is treason.”

Jackson immediately reinforced federal forts in South Carolina and ordered the armed forces to prepare to attack. Tensions were high in South Carolina, with unionists opposing secessionists. To deter South Carolinians from attacking unionists, Jackson said to a South Carolinian congressman, “If one drop of blood be shed in defiance of the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man of them I get my hands on from the first tree I can find.”

Jackson asked Congress for the power to collect tariffs off the coast of South Carolina in what became known as the Force Bill. At the same time, Henry Clay put forth a compromise on tariffs that would gradually lower them. Jackson supported Clay’s actions, and the combination of Jackson’s forceful response to the concept of nullification and his willingness to compromise on tariffs ended the crisis for the moment. However, less than thirty years later, the passions displayed during this crisis led to the Civil War.

>

>